Breadcrumbs navigation

- Home page

- About Moser

- Blog

- We are cultivating techniques that would otherwise disappear, says glass painter Jan Janecký

We are cultivating techniques that would otherwise disappear, says glass painter Jan Janecký

“Wouldn’t you rather go to a café in Liberec? That would not be as messy,” an artist Jan Janecký asks before our meeting. However, he eventually agrees that the interview can take place in his studio. Thanks to this, we have the chance to not only talk about his work, but also watch as the pieces he paints for Moser, among others, come to life.

Jan Janecký lives in Liberec, but his studio is located in the nearby town Nový Bor. Surrounded by a forested landscape and wood-panelled houses, we discover a robust building decorated with a graffiti by Jan Kaláb and Chemis. The construction painted with many rainbow-coloured circles houses the Kolektiv Ateliers, a glass company that Janecký, together with his friends from the field, co-founded in 2012. In the corridors, we carefully zigzag between glass panes of various sizes, and after a while, we come to the door of the studio itself. “So, here's the beauty,” Janecký jokes.

To him, the place has become just a common workspace, but the newcomers certainly find the sight fascinating. The studio greets us with glass kilns, various painted vases, drawings ready for implementation, countless brushes stored in empty jars, and a poster of Vladimír Kopecký, an artist whom Jan Janecký greatly respects. He seats us at one of the many tables, from which he first moves the discarded brushes and dozens of gilded glass components in the shape of an acorn. “I’ll keep working, if you don't mind,” he says. We don’t mind – on the contrary. As we prepare our questions, Jan Janecký sits down at an unfinished vase and begins to paint.

DAD ALWAYS TOLD US THAT THE CRAFT MUST COME FIRST

Your father was a glass technologist, your mother was a painter – and your profession connects the two crafts. Have you always wanted to work with glass?

Not quite. From an early age, I enjoyed fine arts, but my path to glass was winding. When it came time to decide where I wanted to go after elementary school, I wasn't sure. Who would be, at the age of thirteen! My dad always taught us that we must be able to work with our hands first, and then we can study whatever we want. Craft was the most important thing to him. Moreover, it was right after the revolution, and my parents were just starting a glass business. We had a painting studio in the house – similar to this room – and I started helping out on the weekends. I didn't think much of it, a lot of companies at that time were family-owned, so both parents and children took part in running them. But at the age of sixteen, I discovered a new world: Asia. I was captivated by everything connected with the continent, I began to learn languages and took a strong interest in their culture and art. At that time, I wanted to study Japanese studies, but getting to the Faculty of Arts from a vocational school was far from easy. Several unsuccessful attempts at admission followed, and in the end, I stayed with the craft because of my family.

Do you regret it?

No, everything eventually turned out well. I didn’t get a degree in Japanese studies, but Asia is still very close to my heart. Thanks to Moser, I was able to visit a few Asian countries, and I have more travel plans for the future. I would like to return to Taiwan or Japan and stay there for some time. Taipei, for example, was a great place. It connects history with modernity, and when the bustle of the city starts to get on your nerves, you get on the subway and just a moment later, you are on tea plantations surrounded by mountains. But I didn't completely give up on education. This year I completed my bachelor's degree in Jan Stolín’s studio at the Faculty of Arts and Architecture of the Technical University in Liberec. During my studies, I wanted to take a break from glass as the primary material, so I chose to focus on sound in relation to various themes in the environment. As part of my bachelor's thesis, I created an audio-visual soundtrack that reflects my relationship to the Jizera Mountains. Although it is not obvious at first glance, I often use my experience with glass when working with other media. Therefore, I hope that during my master's degree I will be able to connect these worlds and unify glass, painting, gesture, and sound. We'll see.

Your three brothers, including the well-known artist Martin Janecký, also chose glass as their creative medium. Is there any rivalry between you?

Not at all. Martin and I grew up in one room, but we are very different: he is fire, I am water. For example, I was hesitant whether I wanted to devote my whole life to glass, while for him, it was the only choice. The smelter mesmerized him, and eventually, it managed to soothe his fire. Nevertheless, I do not feel that there is any rivalry between us, on the contrary, we help each other. Thanks to his diligence and perseverance, Martin was able not only to push the boundaries of craftsmanship and artistic expression in glass to completely different dimensions, but mainly, his approach and personality inspired a lot of young people to devote themselves to glass. My other brother Petr is a top craftsman who has many years of experience in glass studies in Sweden and South Africa. He now works in a glass studio together with our youngest brother Michal, and we all still cooperate.

I HAVE NO APPRECIATION FOR MASS PRODUCTION IN GLASS

When did your partnership with Moser begin?

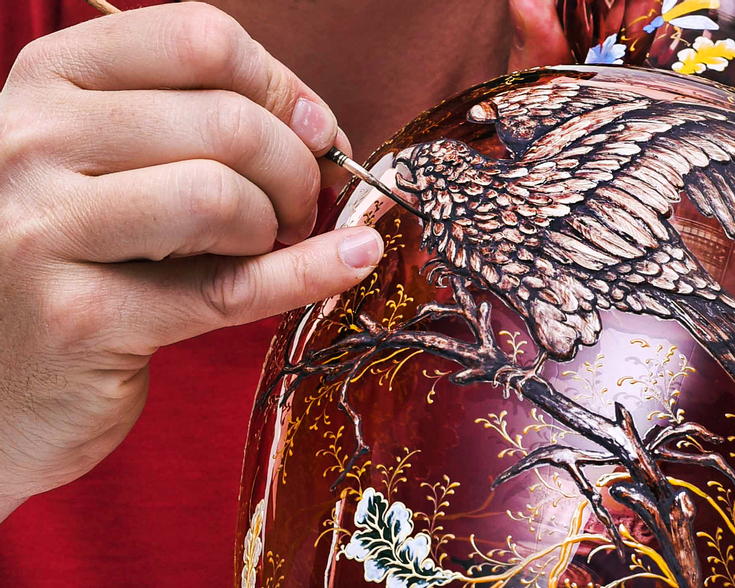

It's been sixteen years. When Moser approached me, I taught painting at the glass school in Nový Bor. They showed me a vase – the same as this one. (Jan points to the work behind his back. The vase is decorated with gold-painted leaves, three-dimensional gilded acorns, and a large painting of a colourful bird with outstretched wings). They asked me whether I could create something similar. I wasn't sure, but I took a shot, and the final result was quite successful. From that moment on, me and Moser cooperated and during our partnership, we have revived dozens of original Moser decors.

Did you work on any other projects at that time?

Back then, I was a teacher, but also a bit of a wage craftsman. A glass painter for hire, you could say. I tried to create a business model similar to other smaller glass manufacturers, but I am not a trader and a series production, no matter how big or small, is not my world. I eventually stayed in my studio, focused on my products, and started working with various companies. At that time, painting workshops were very busy and many of them had no time nor energy to deal with the more craft-intensive tasks. As a result, these assignments eventually came to me, including Moser. I started cooperating with TGK, Preciosa, Lasvit, and I was also externally working on stained glass paintings. Every once in a while, I was told that a client would like to achieve a coloured surface or a glass structure that could not be realised at the smelter and I was asked to figure out how to fulfil the demand by glass painting. My job was to look for solutions to non-standard craft challenges. When Zdeněk Kudláček approached me and my friends in 2012, we founded the company Kolektiv Ateliers, which covers organizationally and technically demanding architectural projects. For instance, the team of Kolektiv reconstructed the glass ceilings of the National Museum in Prague.

Do you find your partnership with Moser special in any way?

I mentioned my "products." I must admit that I don't like the word very much. When someone brings up production, I imagine the 1990s and the demand to manufacture a large number of identical glass painted objects. I appreciate that the projects I'm involved in for Moser are, in a sense, rare. They are only produced in limited series and the brand puts a great emphasis on precision and detail.

The skilled hands of Jan Janecký paint precise works full of detailed natural motifs, but he himself is primarily attracted to contemporary and abstract art. A painting by Štěpán Hortenský hangs on a wall of his studio. On the canvas, we can observe a realistically portrayed sea surface and a vivid sky, while sharp geometric lines emerge from the horizon, their red-yellow colours contrasting with the blue scenery. It could be claimed that the painting itself embodies the opposites that meet in Jan Janecký. "The traditional paintings I create for Moser would have become extinct without the glassworks. That would be a such pity,” the artist explains. However, when we ask him to pick a piece by Moser that he would use to decorate his own interior, he mentions the modern geometric collections of the pair Ingrid Račková and David Suchopárek, or the pieces by Lukáš Jabůrek and Kateřina Doušová. "Their works have a distinctive artistic language and they ‘work’ regardless of the material. I would definitely choose between them,” he replies.

If you were to compare the process of glass painting with painting on paper or canvas, could you name any particularities of your craft?

First off, glass is slippery! When I taught at the glass school in Nový Bor, the differences between glass and paper were the first question we dealt with in class. There are many differences. A fundamental one is that glass reflects light, so you need to work in a suitable environment to see the decor. For example, now I don't see anything at all! (He laughs and points at the black vase in front of him, on which the midday sun's rays fall and their reflection hides the unfinished motif.) Unlike paper, glass also does not absorb colour, so it must be handled differently. Glass painting is created by layering thin coloured surfaces and each piece passes through a series of firings between the individual layers. I actually have to break down each decor into components and think about how to arrange them so that the result looks good. We must also take into account the three-dimensionality, fragility… My craft is simply so specific that although I can easily paint on glass, I might not know how to handle working with paper or canvas.

You have been painting on glass ever since you were a child. Are the skills that you have gathered throughout those years all that you need, or do you still have to learn?

There is always room for improvement, learning is a never-ending process. My experience with teaching – a discipline that I would like to return to one day – has taught me a lot about the craft and the possible approaches to it. My students exposed me to different perspectives on art and life, and I would say that teaching keeps me in a certain mode of presence. I enjoy the world of art in general, regardless of the material and the method. Thanks to Maxim Velčovský, I had the opportunity to work with Vladimír Kopecký. We spent several weeks together in a studio working on vases and sculptures which were to be seen at his retrospective exhibition in Kampa. I view Kopecký as an incredible personality, both artistically and character-wise: he studied with Kaplický, gained education in traditional realism, and gradually worked his way to pure abstraction. At the same time, he also reassured me that what I do for Moser makes sense, because in addition to experimenting in freelance work, it is important to keep the craft alive.

LUDWIG MOSER KNEW HOW TO RESPOND TO THE AESTHETICS OF HIS TIME

How do the works you paint for Moser come to life?

The story of Moser lies behind each piece. Although Ludwig Moser initially did not own a glasswork, he proved himself to be a perfect businessman. He was also a great designer who responded to the aesthetics of his time. He invented decors which he then assigned to painters in Harrachov. This is where the works that we are trying to revive in the studio today were created. We only have limited resources: in the Moser archive, there are drawing books that I can look into, and some works can be traced at auctions. I take my inspiration from drawings, photographs, and whenever I can, I go to the museum depository and inspect the originals to study the techniques and procedures used.

Are you trying to imitate the originals to the very detail?

It depends, but some features cannot be replicated because there is no comprehensive documentation. If you put the original and the current replica side by side, I dare to say that our work is sometimes more delicate and precise. The original vases, in turn, have non-transferable energy. Oh, the dynamic they have! Painters of the time were masters of their field. In the drawing books, we see that sometimes the artist only sketched three precise strokes – and a realistic bird appeared on the paper. The originals simply have a vigour that is difficult to imitate.

The latest works you have painted for Moser include the Cora, Aquila, and Scarlett vases. What was it like working on them?

Cora, in particular, was a tough one. The entire surface of the vase is optically structured from the smelter. As a result, the paint flows into the individual structures while we work,

and it is difficult to keep the colours under control. The result was beautiful, yes, but the specific surface required a patient approach and immense precision. However, the same can be said about Scarlett and Aquila. These particular pieces were not complicated because of the structures, but due to the complexity of individual decorations. The decors which we otherwise paint on larger areas had to be transferred to the vases in the same detail, but in a much smaller scale.

How long does it take to create such laborious replicas?

It is hundreds of hours of work. But I would like to emphasize that I am not the only person doing the painting. If needed, I could probably decorate a replica without help, but I cooperate with a great team of people that participate in the creation of each piece. We have all found what’s "ours" in the craft – something we enjoy the most. And so, I can focus on more demanding details or solving the process of painting technology, someone else will take care of gilding, another person is dedicated to relief painting… I am very happy for the teamwork.

How would you like glass painting to progress in the future?

I praised Ludwig Moser for responding to the aesthetics of his time. But after the Art Deco period, the continuity in glass painting somewhat disappeared. For example, geometry is now employed mainly in engravings or grinding. Glass painting may seem cumbersome to many, so the craft is mostly left with traditional designs. There is a logical reason behind this: it is precisely in traditional and historical themes that the artistic possibilities of glass painting stand out the most. Of course, I'm grateful that Moser values their history and keeps the original techniques alive. But I believe that there is room for innovation. Moser could, for example, approach a prominent contemporary artist – a person with an attractive art language, even someone completely outside the glass scene. Marcel Wanders or Jaime Hayon and their fresh approach to "decor" come to my mind right away. Their works would suit Moser well. Such partnership would push the glassworks forward and it could help Moser to get their pieces “out of the showcases”, as the new artistic director Jan Plecháč puts it. I like his approach and I'm curious in the development of the glassworks under his leadership.

Jan Janecký

artist, glass painting specialist

Jan Janecký lives in Liberec. His studio in Nový Bor is also the headquarters of Kolektiv Ateliers, a company which he co-founded in 2012 with his friends. He studied glass painting at the glass school in Nový Bor, where he later worked as a teacher for 8 years. He has now completed a bachelor's degree at the Faculty of Arts and Architecture of the Technical University of Liberec. He has been cooperating with the Moser glassworks since 2006, creating richly decorated replicas of vases from the turn of the 20th century. His pieces are unique works of art, the realization of which takes several months. He also collaborates with other brands, such as Lasvit or Sans Souci. When he is not painting on glass, he spends time in his sound studio, where he devotes himself to audio-visual creation.